The truth about penicillin allergy

The truth about penicillin allergy

05 Sep 2023

Research shows that one in ten people who present to hospital self-report penicillin allergy, when in fact less than one percent of those are actually allergic.

Without a proper diagnostic approach, many patients who have labelled themselves as having a penicillin allergy may unnecessarily receive less targeted, broad-spectrum antibiotics, leading to an increased risk of hospital-acquired infections, and higher length of stay.

But studies reveal that when people with a self-reported penicillin allergies are properly allergy tested, they have no reaction and should be ‘de-labelled’.

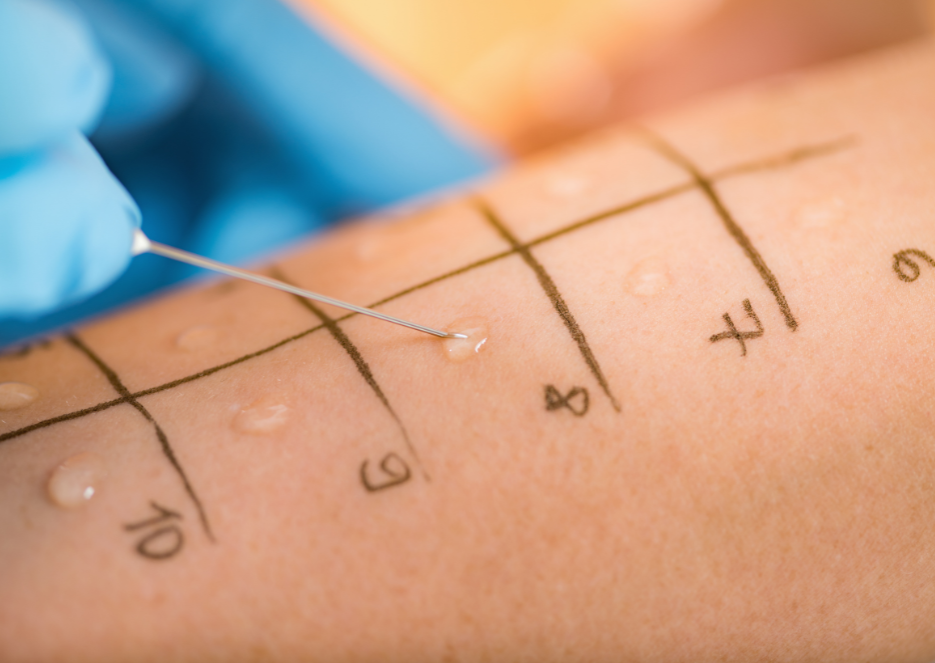

“When you go to the trouble of skin testing and challenging people, around 90 per cent don’t actually have penicillin allergy. One problem is that it’s so much work to do all of that safely,” says Dr Winnie Tong, St Vincent’s Clinical Immunologist and UNSW allergy researcher.

So why is penicillin allergy so over-reported?

“Many patients say their parents told them. For example, one person has a reaction and the parents are concerned others in the family could be allergic, even though penicillin allergy is not inherited,” Dr Tong says.

Even for patients who experienced a penicillin reaction in infancy, will no longer have the allergy over time, in fact 80 per cent of patients will have lost sensitivity to the drug after 10 years.

“Medicine is a risk averse system. It’s very easy to label someone as allergic, and tell them to avoid penicillins for the rest of their life,” Dr Tong says.

“But it’s very difficult then to safely say to someone, you can take away that label, and you can have penicillins.”

The multi-site research team headed up by Principal Investigator, Prof Andrew Carr, a Clinical Immunologist at St Vincent’s, addressed patient comprehension of penicillin de-labelling amongst inpatients. In brief, more than half of the patients with self-reported penicillin allergies, who’s tests results showed they in fact had no adverse reaction to penicillin, did not trust the results.

However, when patient communication included verbal discussion of results on the day of testing, results letters, updating of electronic medical records, and supply of medical alert jewellery if required, that figure rose to 92 per cent.

These findings show that clear, standardised communication with patients is crucial so that they understand their penicillin allergy status.

Now in 2023, the researchers are checking in with patients from the trial to understand whether the advice provided about antibiotic use has stuck. For example, if a patient was de-labelled, are they now comfortable using penicillins?

These are complex issues, not to mention ongoing challenges around cost and wait times for allergy testing. But according to Dr Tong, simply raising awareness with the public about penicillin allergy makes a difference.

“I want people to understand that saying you’re allergic to penicillin has been demonstrated to lead to poorer outcomes, in particular when you end up in hospital. The more awareness we have, the better for patient care.”

Click here for the full research paper.

This research was originally published in UNSW News