Anal pre-cancer (anal intraepithelial neoplasia)

General information about anal pre-cancer

The term “anal pre-cancer” is used to describe conditions which, in a small minority of people, can progress to cancer. The rate of progression from pre-cancer to cancer is not known, but may be of the order of 1 in 4000 per year for HIV negative people and 1 in 400 per year for those with HIV.

The term “High grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (HSIL)” is used to describe the microscopic appearances of pre-cancer. Sometimes HSIL is divided into two forms, called Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN), grades 2 and 3. Grade 3 is regarded as more serious than grade 2. Many AIN1 lesions are regarded as benign and are very unlikely to progress to cancer.

Where does HSIL occur?

Anal HSIL may be described according to where it is found:

- Perianal – when it develops just outside the anus, within 5cm of the edge of the anus

- Intra-anal – when it occurs inside the anus, mostly within the first 5cm inside the anus

It is possible to have anal HSIL in both sites at the same time.

What does anal HSIL mean for HIV-negative gay men?

Around 30% of HIV-negative gay or bisexual men have anal HSIL. Most people are unlikely to be aware they have the condition, unless they have special tests performed on the anus It has been estimated that around 1 in 4000 such men will progress to cancer each year.

What does anal HSIL mean for HIV-positive gay men?

Around 40% of HIV-positive gay or bisexual men have anal HSIL. Most people are likely to be unaware they have the condition, unless they have special tests performed on the anus It has been estimated that around 1 in 400 such men will progress to cancer each year.

What does anal HSIL mean for women?

A small, unknown, proportion of women develop anal HSIL. It is approximately 10 times more common in women who have a history of HPV-related abnormalities in the cervix, vagina or vulva.

HIV-positive women are also at higher risk. It is important that all HIV-positive women have regularly cervical Pap smears.

Who else is at risk of HSIL?

Cigarette smokers have increased risk of developing anal cancer. Stopping smoking is important for all people, particularly those diagnosed with HSIL or anal cancer.

People with problems of their immune systems may be at increased risk of anal cancer. This includes people who have had an organ transplant or conditions like systemic lupus.

What are the symptoms of anal HSIL?

Most people who have anal HSIL have no symptoms and don't know they have it. If symptoms do occur, they include discolouration of the skin, itch, pain, lumpy skin or bleeding.

What causes anal HSIL?

Anal HSIL may occur following infection with certain “high risk” HPV types, especially type 16. Anal warts are more typically due to different types of HPV (“low risk”) types – these are most commonly types 6 and 11.

What is Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)?

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world. Anogenital HPV infection is divided into two groups:

“High risk” types, of which HPV type 16 is the most common. Other high risk types include types 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82.

“Low risk” types, of which HPV type 6 is the most common. These are most often associated with benign anogenital warts. Other low risk anogenital HPV types include HPV 11, 42, 43, and 44.

How common is HPV and what are the symptoms?

Because infection is so common, most people encounter HPV very early on in their sexual careers. The majority of people infected with HPV have no symptoms or signs and their immune systems successfully get rid of it, without the person ever being aware that it has happened. However, in a minority of people, the infection persists. A minority of those with persisting HPV infection can then go on to develop symptoms or HSIL.

Warts typically appear as single or multiple soft, moist, or flesh-coloured bumps in the ano-genital areas. They sometimes appear in clusters that resemble cauliflower-like bumps, and may be raised or flat, small or large. Simple warts are essentially a cosmetic problem and are not generally regarded as pre-cancerous.

How is HPV transmitted?

HPV is very infectious and is spread by skin-to-skin contact during oral, vaginal, or anal sex with an infected partner. It can also be spread by non-penetrative sex, such as touching with hands. Recent evidence suggests that it can be spread from the vaginal region to the anus in women by wiping. This suggests that women should generally wipe “from back to front”, rather than “from front to back”, to avoid transmitting HPV to the anal region.

How can transmission be prevented?

The only way to prevent getting an HPV infection is to avoid direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected person. Using condoms may partially reduce your risk of HPV. However, condoms do provide excellent protection against other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

Should I get vaccinated?

Gardasil 9 is the vaccine currently available in Australia. It provides excellent protection against the main high risk HPV types, including HPV 16. However, it must be given before initial exposure to HPV. As most people encounter HPV soon after becoming sexually active, this means that the vaccines should be given as early as possible. This is why schools-based vaccination programs are the most effective.

Current evidence suggests that the vaccine is is likely to work in men under the age of 26 years and women under the age of 45. It is unclear whether it is worthwhile getting vaccinated at older ages. It is occasionally recommended for older people, depending on their circumstances

How is HPV treated?

Currently there is no known cure for HPV infection.

Genital warts sometimes disappear without treatment, but there is no way to predict whether warts will grow or disappear. There are several creams and solutions available for their treatment, depending on their size and location. Some lesions may also be treated by freezing, burning or laser treatment. Although these treatments remove the warts, they do not necessarily remove the virus. Thus, as HPV may still be present after such treatment, and warts often come back.

People who smoke cigarettes may respond less well to treatment.

Can I get tested for HPV infection?

Testing for high risk HPV infection is now performed as part of cervical screening procedures, and to monitor response to treatment. Its role in the diagnosis and management of anal conditions is currently under evaluation.

What tests can be done to diagnose anal HSIL?

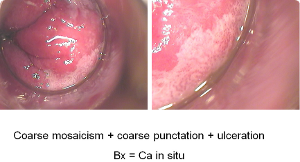

- Inspection: Close examination of the external anal area by a specialist can sometimes suggest a diagnosis of HSIL. However, changes can often be very subtle and easily missed. Internal anal HSIL can rarely be diagnosed by looking at the area, even when using an instrument such as a proctoscope.

- Anal Papanicolaou (“Pap”) smears

- High Resolution Anoscopy (HRA)

- Biopsies: These may be taken from the outside of the anus (perianal biopsy) or internally.

How is anal HSIL treated?

A large majority of people with HSIL never develop cancer. However, all HSIL cases must be taken seriously and it is important to discuss matters carefully with your doctor, to see what options are best for you.

The ANCHOR Trial has demonstrated that treatment of anal HSIL in people living with HIV leads to a marked reduction in progression rates to anal cancer. However treatment is technically complex and currently has limited availability. Treatment options include:

-

- No treatment. The vast majority of anal HSIL never progress to cancer. However, close observation is necessary, to ensure that any changes are detected early

- Surgery. This is reserved for the larger lesions that have features suggesting they are likely to progress. Whilst the treatment removes the lesion, surgery may cause damaging scarring and recurrences can occur

- Other physically ablative methods. This includes electrocautery, infra-red coagulation and laser. These are less likely to cause long term problems than surgery, but require repeated treatments using High Resolution Anoscopy. Recurrences are common.

- Application of creams such as imiquimod and podophyllotoxin. These are most commonly used for perianal lesions, as they can cause significant burning. Recurrences are common.

Your specialist will be the best person to discuss which approach is the most appropriate for you.

What should I do if I am worried about anal HSIL?

Talk things over with your doctor, who will perform an initial assessment. If necessary, then you can be referred to a specialised service. If you are uncomfortable about talking over such matters with your doctor, Sexual Health Clinics often offer very useful advice.

More information is available at a number of sites, including:

http://www.thebottomline.org.au/

https://www.iansoc.org/Patient-Support

http://www.analcancerfoundation.org/